Photo borrowed from Anger Management Resource (http://www.angermanagementresource.com/)

We all have to put in the time and effort to build positive relationships with students. I’ve recently been working with some staff on building positive relationships with the students in their classroom. Pairing, a process of associating oneself with positive reinforcement through consistently matching yourself with positive stimuli, is a helpful strategy to building (and rebuilding) relationships with students.

Whether it’s a home program or within a classroom, pairing can help establish the relationship between teacher and student. I think pairing is a key component at the beginning of any behavioral program and is essential to the failure or success of your program.

One of the basic premises behind a behavioral program is that students will be much more motivated when they are having fun. Therefore, as a teacher or therapist, you must become fun for the student. Pairing is used to help the child get used to the teacher/therapist and look forward to teaching/therapy sessions. A good way to establish instructional control is for teachers to first connect themselves with positive reinforcement. It begins with noncontingent reinforcement. In other words, the student is first reinforced without having demands placed on him or her. This initially could be in the form of a compliment or tangible item (it depends on what is motivating to the student).

In the beginning, the only requirement for getting access to reinforcement (besides the lack of undesirable behavior) is that the student take the reinforcers from the teacher. Technically speaking, the reinforcement is still contingent, as there must be an absence of undesired behavior (tantrums, aggression, SIB, etc.) for reinforcement to be delivered. However the focus for the teacher/therapist is to seek and provide as many positive reinforcement opportunities for the student as possible.

After this is happening consistently (after several hours or even days), the teacher/therapist must gradually fade in demands; slowly increase the response requirement before reinforcement can be given. Eventually the teacher/therapist will be able to gradually present more demands of varying difficulty. Successful pairing will help ensure the reinforcement value of learning is not lowered while at the same time preventing the increasing the value of escape.

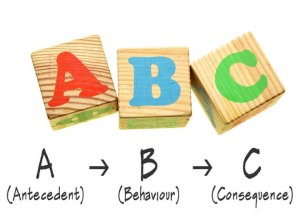

Pairing essentially involves 3 elements which must be in close association with each other:

1) The student The learner who is seeking positive reinforcement

2) The teacher/therapist Becomes the conduit by which the student obtains reinforcement.

3) The student’s desires and reinforcers. The student has to want it, or it’s never going to work.

In order to become a reinforcer themselves, a teacher or therapist will have to capture and contrive MOs/EOs and identify strong reinforcers with which they can be paired. Often times this may mean providing limited access to reinforcing items to certain times of day or under certain conditions in order to increase the desire to obtain them. A teacher/therapist may also have to contrive the setting under which this occurs (such as a space with increased likelihood to obtain reinforcement, such as play areas, play centers, etc.). Once this happens, everything associated with the teacher, especially learning itself, becomes reinforcing.

Whether you are a teacher, therapist, counselor, paraprofessional, administrator, or parent; your position alone does not automatically make you a reinforcing person in a student’s life. Pairing is a systematic way to help you establishing trust and connect yourself with reinforcement. It is this association with that solidifies the child’s view of the therapist as fun and reinforcing. The teacher/therapist becomes a bridge between the student and reinforcers.

This is a simple description of how the pairing process can be implemented in the classroom or at home. I will expand on this in a future post. This is not intended nor shall it be misconstrued as advice. As always, before engaging in any any major behavior change program you should consult an expert or highly trained professional such as a Board Certified Behavior Analyst.